The magic world of EVPN and VXLAN (EVPN and VXLAN Episode 1)

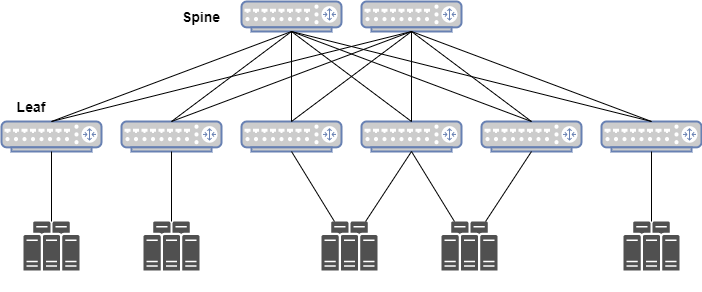

My journey with EVPN and VXLAN started more or less a couple of years ago, when I had to create a Datacenter Fabric for a customer with 2 Spines and 6 Leaf “clusters” (for a total of 12 physical leafs). I had to architect it for supporting both Layer 2 and Layer 3 services (with Type-5 routes).

Since the first days, I found this an “efficient” and “effective” technology, which gave me the option to unify the control plane for layer 2 and layer 3 services in a datacenter fabric. Basically, one protocol to rule them all. It is also efficient in creating an “abstraction layer” for the forwarding plane (i.e., VXLAN, MPLS, …), even if I used it only with VXLAN.

However, this and other later deployments I did, were on proprietary hardware and OS, and were totally mono-vendor (and also, same vendor for all the deployments).

I started writing some notes about it, and I also plan to test some other vendors’ configuration, multi-vendor interoperability, also with open source products.

So, here we are.

But, first of all, let’s take some steps back.

What is EVPN? And what is VXLAN?

EVPN is a protocol extension (address family) for BGP. It has AFI/SAFI = 25/70, so it is a sub address-family of L2VPN (AFI 25).

BGP EVPN was initially developed for MPLS Carrier Services for Layer 2 applications, as a “VPLS on steroids”. Many people know it for its “announce MAC addresses as routes” feature, but it is much more.

Also, one of its differences with the classic Layer 2 or Layer 3 “plain” VPN services, is that EVPN is not strictly bound to an MPLS data plane: in fact, MPLS is only one of the possible transports, as well as VXLAN is.

VXLAN? Is it a VLAN with a spelling mistake? What’s that beast?

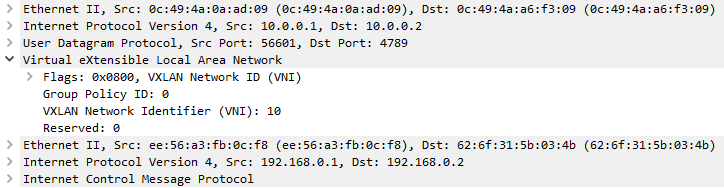

VXLAN stands for Virtual eXtensible LAN… but it’s not only that. It’s more like a tunnel, over IP encapsulation (with UDP), like GENEVE, GRE, L2TP, and many more. VXLAN transports ethernet frames, but that’s only an encapsulation detail. And, yes, you can use BGP EVPN to signal the VXLAN dataplane state.

In fact, VXLAN and EVPN became the de-facto standard dataplane/control plane for all the modern Datacenter Fabrics, and there are many many vendors supporting it.

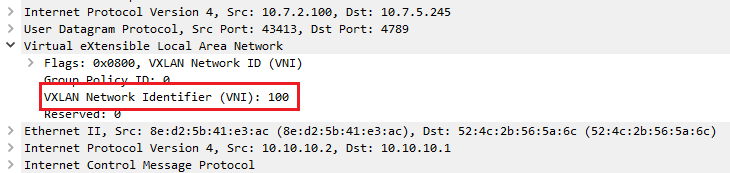

Let’s dive a bit deeper inside VXLAN. VXLAN is defined in RFC7348 as a VLAN-like encapsulation method, but over IP/UDP (port 4789). The most important parameter of the VXLAN protocol is the VNI, which is the Virtual Network Identifier. You can see it as a VLAN tag for the VXLAN packets, with the difference that its value size is 24 bits (0-16.777.215). More than 16 million VNIs are possible!

VXLAN endpoints, which terminate VXLAN tunnels, are known as VXLAN tunnel endpoints (VTEPs) or Network Virtualization Edge (NVE).

I was talking about “Fabric”, “Spine” and “Leaf” before. What’s that?

A datacenter fabric is like a hub and spoke topology, where the Spine is the hub, and the Leafs are the spokes of the network. In a EVPN/VXLAN Datacenter Fabric, the spines are responsibles for forwarding the IP packets between the different Leafs, which are the VTEPs. You can see the Leafs as the PE/LER of a traditional MPLS network, and the Spines as the P/LSR routers.

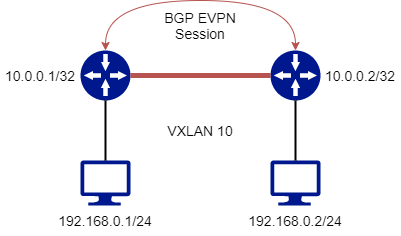

As a first step, let’s see a very quick configuration. I will create a direct connection between two Dell OS10 Virtual Instances, as two Leafs. I am making some simplifications (i.e., no Spines, direct BGP peering) just to demonstrate some basic features. Later on, we will add additional constructs that will allow us to properly grant the network scalability, and we’ll also add some redundancy levels as well.

The two devices are configured with a Loopback interface/address, reachable via static routes, that will be used for BGP EVPN session and as VTEP Address (usually, the BGP sessions are separated from the VTEP Addresses).

The configuration on the two Dell OS10 devices is quite simple: (reporting only the relevant part of one of them)

hostname SW-1

!

bfd enable

!

virtual-network untagged-vlan 4090

!

interface loopback0

no shutdown

ip address 10.0.0.1/32

!

nve

source-interface loopback0

!

interface ethernet1/1/1

no shutdown

switchport mode trunk

flowcontrol receive off

!

interface ethernet1/1/9

no shutdown

no switchport

ip address 10.255.255.1/30

flowcontrol receive off

!

ip route 10.0.0.2/32 10.255.255.2

!

router bgp 65000

maximum-paths ebgp 4

maximum-paths ibgp 4

router-id 10.0.0.1

!

template ibgp_session

bfd

remote-as 65000

send-community extended

update-source loopback0

!

address-family l2vpn evpn

activate

!

neighbor 10.0.0.2

inherit template ibgp_session

no shutdown

!

evpn

auto-evi

disable-rt-asn

!

virtual-network 10

member-interface ethernet1/1/1 untagged

!

vxlan-vni 10

!

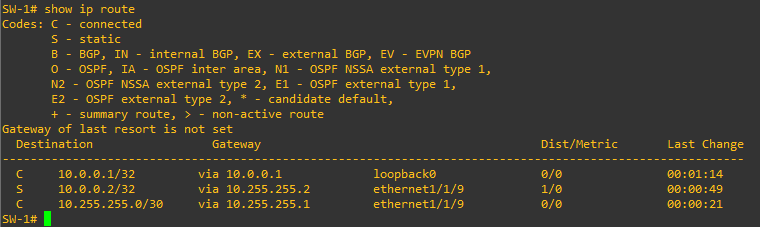

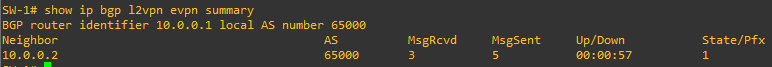

Let’s verify the setup: we can confirm that the BGP session is up:

and we can see the two VTEPs discovering each other, using “special” BGP announcements, called “Type-x Routes” (we will discuss in details the different EVPN Route Types on a next episode):

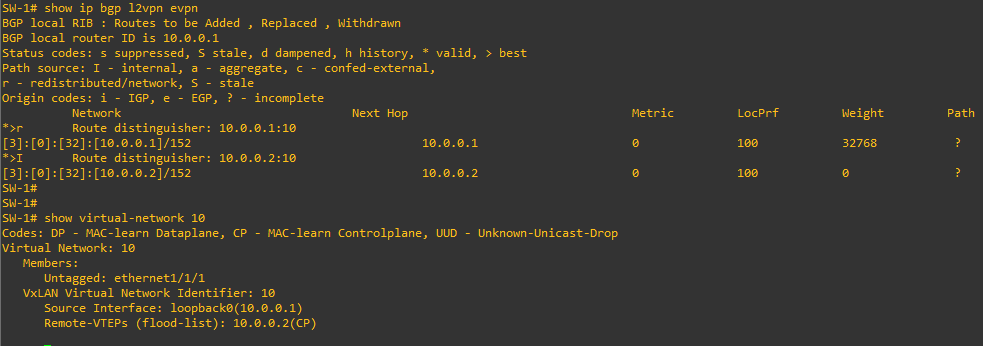

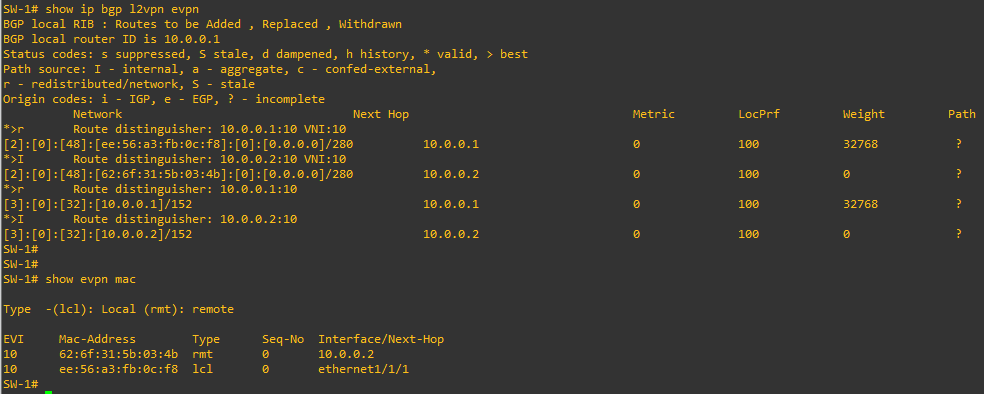

We said that EVPN is able to “announce” the MAC addresses of the connected hosts using BGP. This is done by EVPN “Type-2 Routes”:

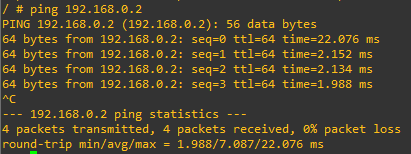

Well, to be honest these entries appeared only after I configured the two hosts and tried a ping:

Which we can see also on this trace:

I think we are set, for now. In the next episode we will dig into the different EVPN announcements (Route Types), focusing on Type-2 and Type-3 Routes. We will also try a simple setup with a different vendor.

See you soon!